The curated and public “rinsta” — a portmanteau of “real” and “Insta” — is maybe the most popular unofficial category of Instagram accounts. But a new type of rinsta has been brewing: Rice-related Instagram accounts. Focused on subjects from possums to bricks, these accounts show an oddly specific aspect of life on campus. The Thresher talked to the owners of three of these accounts.

When the pandemic hit, one of the first things to go was the in-person campus tour. The familiar sight of a student tour guide walking backward through the Rice Memorial Center was replaced by virtual tours. But this year, in addition to virtual tours, in-person campus tours are back — albeit not exactly the same as they used to be.

Dogs, cats, fish: these are just some of the animals that live with us on Rice campus. Coexistence alongside noisy college students, bustling student-run businesses and constant construction isn’t the typical life of a pet -- the ones that do reside here are special in this way. The Thresher met 12 pets and interviewed their humans to learn about their lives on campus.

Are you a freshman new to Houston? Technically a sophomore but lived remote last year? A senior looking for new places to try before you graduate? And whatever the juniors are up to, we’ve got you covered. Our staff has compiled H-Town recommendations for you, from bars to barber shops and everything in between.

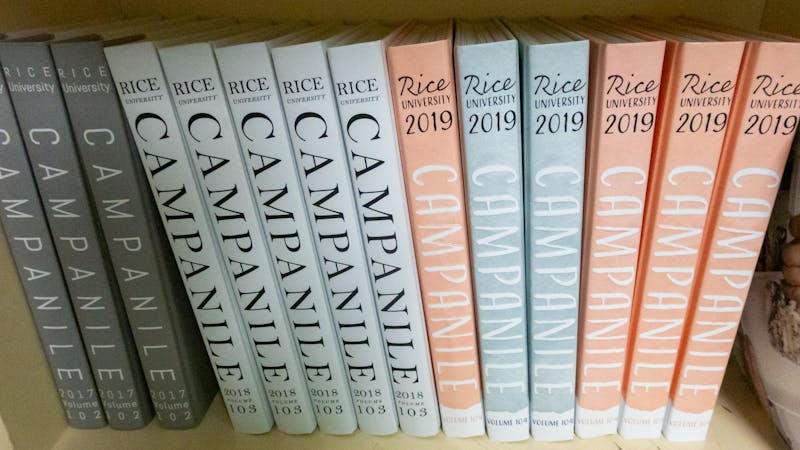

Rice’s undergraduate population has the opportunity to join clubs ranging from STEM-focused organizations to writing-intensive publications. Rice’s very own student-run undergraduate yearbook, the Campanile, falls under this wide spectrum. The Campanile has evolved in many ways since its early years. More than just a yearbook with headshots or a box of items, it is now a collection of stories and senior photographs — a history of the academic year and a record of student voices.

There are different stories behind Diwali, a Hindu holiday that usually falls in October or November. One such tale describes the god Krishna’s defeat of a demon on that day and another tells of the return of the god-king Rama after defeating a demon. Regardless of the story behind the holiday, Diwali is about the triumph of good over evil, according to Will Rice College junior Vaishnavi Movva. She said Hindus celebrate by praying in the temple for prosperity for the year and lighting up little lamps called “diyas” outside their homes.

In the history of the Rice Thresher, the publication of print editions has been suspended three times: last February in the midst of a historic winter storm, in spring 2020 during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States and in 1918 during World War I — and the coinciding Spanish influenza pandemic. The last edition of the Thresher in 1918 was published May 25. Thresher staff wrote about the establishment of the Student Association and the poor quality of food during wartime and published advertisements, aimed at the student body of a militarized campus, for military uniforms for sale.

When a student walks into Fondren Library, a lot of factors go into choosing their studying location — the amount of natural lighting, the comfiness of the chairs or maybe someone cute sitting nearby. Recently, Fondren has started sharing another factor to consider before students even enter the building: crowd levels, posted online and at Fondren’s entrances.

There is no linear path to take in life and in college — no one-size-fits-all plan to success. Sometimes, the unexpected happens (say, a global pandemic). Or you simply decide to step back and re-evaluate what would be best for you, regardless of what others say you should be doing. Taking a gap year is a choice that students make for a multitude of reasons. The Thresher talked to six students who took last year off from school to learn more about the unique experiences they’re bringing back with them.

Anyone who has attended a Rice campus tour has heard stories about how students use their Tetra points, which are $1 points that can be used at on-campus restaurants and cafés. Some seniors spend their four years at Rice hoarding Tetra to save up for a dog from the Rice Farmer’s Market before graduation — so say the tour guides, at least. But not everyone is fortunate enough to conserve their Tetra for a full year, or even a whole semester. If your student ID is burning a hole in your wallet and you’re looking to (affordably) spend on meals outside the serveries, look no further than this list of Tetra-accepting food and drink options available on campus.

After more than a year of learning via Zoom lecture, Max Yu, Victor Song, Kaichun Luo and Lorraine Lyu were well-equipped to recognize flaws in this key component of pandemic education. Last Friday, they decided to make an improvement to the system. Together, the four students coded Thoth, a tool that makes both Zoom lectures searchable and manageable by condensing 40-minute recordings into pages of notes.

Despite the high COVID-19 vaccination rate on campus, the pandemic has continued to disrupt life at Rice. Last month, new students matriculated anticipating a relatively normal year. Hopes were quickly dashed as on-campus COVID cases increased during Orientation Week, and some students had to isolate or quarantine. The Thresher spoke to three new students who spent part of O-Week in isolation.