The Road to Integration

Although the Rice Institute should logically be among the first to integrate it will probably be among the last.”

The Thresher editorial board published this statement in 1957 on the heels of the recent integration at the University of Texas. The writers were unaware of their surprising foresight, as they wrote eights years before the first black undergraduates matriculated.

When William Marsh Rice wrote the 20-page charter creating Rice, he left the provision that the school be a “means of instruction for the white inhabitants of Houston.” It was not until 1965, when the need for money outweighed the revered charter, that Rice felt pressure to integrate and begin charging tuition.

On Rice’s path to integration, although the Thresher was not a driving force, it served as a platform for activism, chronicled the community’s opinions and advocated for integration years before others would do the same.

The early days

The first mention of integration in the Thresher appears in coverage of an isolated incident in 1928, when students at a pre-law banquet received a hoax letter suggesting that Rice integrate. The students at the meeting held a frenzied symbolic 14-5 vote in favor of segregation. The Thresher reported the occasion sensationally, stating “true Southern blood begins to boil” at the thought of integration.

The Thresher staff’s own attitude on race in 1935 then became apparent in its satirical publication the Fresher, which bore the headline “Dogs are Much More Costly Than N-----* in Panama” on the front page.

As with any publication, the Thresher’s outlook changed with the editors and the era, but in its early days the Thresher amplified the overtly racist views of much of white America at the time.

1948-1949: Tyson’s Thresher

However, the same publication that spread bigotry began a discussion around integration nearly a decade before Rice’s board of trustees considered admitting black students. Editor in Chief Brady Tyson (’49), who later went on to be a civil rights activist with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and diplomat under the Carter administration, passionately advocated for integration on the Thresher’s pages in 1948.

“The Christian sense of the people of the South, will, at last, become disgusted by such a hate campaign,” Tyson wrote in September 1948, in reference to South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond’s ad campaigns against integration.

Thurmond provided a response to Tyson’s comments in a letter to the Thresher, where he stated each individual state should have the right to determine whether to desegregate.

“I, myself, believe that separation of the races is necessary in my own state for the welfare of both white and colored,” Thurmond wrote.

Tyson went on to use his position as editor in chief to push coverage of race relations, leading some to call for his impeachment.

In December 1948, the Thresher interviewed Heman Marion Sweatt, an African-American who sought entry to University of Texas in a case that ultimately reached the United States Supreme Court in Sweatt v. Painter. Some readers saw the move as the Thresher’s unspoken support of integration at Rice.

“Just what was the purpose of this article?” Coy Mills (’25), the principal of Houston’s Jefferson Davis High School whose son was attending Rice, wrote in a letter to the editor. “What will be your attitude if Sweatt or another Negro is admitted to Rice and tries to date … your best girl friend or sister?”

The Thresher’s editorial board responded to Mills in boldface, writing, “Students who apply for admission to the Institute should be judged equally and solely upon scholastic qualification and capabilities.”

Over the next few months, Tyson’s Thresher responded to anger from not just the Rice community, but from all over Texas, with some labeling him an “extremist.” However, Tyson was not without support — the executive secretary of the Houston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People sent Tyson a private letter of encouragement.

Ultimately, Rice President William Houston ended any discussion around integration at Rice in an 83-word letter to Tyson published in the Thresher.

“The Rice Institute was founded and chartered specifically for white students,” Houston wrote. “The question of the admission of negroes is therefore not one for administrative consideration, and the discussion in this connection is entirely academic.”

This letter was so impactful that the New York Times cited Houston’s words. Despite Houston’s attempts to shut down the conversation, the Thresher continued to reprint editorials and news from other universities on desegregation.

The Rice Institute would continue citing the charter as reason not to integrate for several years, even as the world around them changed.

An insulated community

The Rice Institute of the mid-20th century was an entirely different university than it is today. The school was largely funded through its investment in the Rincon oil field in Starr Country, Texas, which produced $35 million for Rice from 1943 to 1978. Because of this funding source, Rice did not take federal government funding, which would be accompanied by mandates for equal access.

Student polls revealed shifting opinions over time. In 1953, 51.6 percent of students supported admittance of black students, while 39.4 percent opposed it. Four years later, 32.7 percent favored immediate integration of Rice and 28.7 percent supported eventual integration out of a total 522 votes.

However, administrators also had little reason to act on student opinion. Rice Centennial Historian Melissa Kean said that, because Rice did not charge students tuition, the university felt little obligation to take their concerns seriously. Kean has also conducted extensive research on integration for her book, “Desegregating Private Higher Education in the South.”

“When the students aren’t paying to be there, there is a different mindset in place,” Kean said in an interview, marking the contrast to student’s current expectations of control over Rice’s culture. “[The mindset] was not one that was inclined to take particularly seriously student opinion about any issue, let alone something as explosive as race relations.”

Regardless, the Thresher continued to occasionally publish on the controversial topic. In 1950, the Thresher reported that a flaming cross appeared in front of the UT Law School building that Sweatt attended after winning his case. The letters KKK were “daubed in red paint in over a hundred places throughout the law school building.”

“It will not be so many years, we feel sure, before the Rice Institute will admit qualified Negroes, whether under orders from the courts or voluntarily,” the Thresher warned, condemning the Klan and reflecting on the fight on segregation that happened in its pages a little over a year before. “When this comes about, Rice and Rice students will be on trial just as surely as are Texas and Texas students now. It can happen here.”

Years passed, and the change did not come. In October 1954, Cornell University’s student paper requested that Thresher staff help with securing equal sleeping and eating accommodations for a black student on the football team, Dick Jackson, during a road game at Rice.

“Unfortunately we had to reply that regardless of our personal feelings and regardless of the United States Constitution and the Bible, the State of Texas maintains that this athlete is inferior (incidentally, the inanity of this contention was adequately demonstrated on the playing field Saturday night) and not entitled to equality with his white teammates,” the Thresher wrote in an editorial. “Thus again we must hang our heads in shame.”

Turmoil on the board of trustees

Unknown to those outside the board of trustees, Rice had begun feeling federal pressure to desegregate. In 1954, the Atomic Energy Commission, which provided funds for Rice’s physics department, notified Rice it had to comply with nondiscrimination policies. President Houston circumvented this requirement through a loophole by allocating the AEC-funded equipment toward fourth- and fifth-year students, none of whom were black.

“If no blacks met this condition, Houston reasoned, no blacks could be discriminated against,” Kean writes in her book. “The fact that the reason no blacks met the condition was because Rice discriminated against them in its admissions process seems not to have occurred to him.”

Despite exploiting this loophole, Houston understood that government funding was fundamental to university development. Rice’s request to build a federally funded reactor on its land was rejected, and its proposal for a NASA research building on Rice land stalled, both partly due to federal requirements on integration.

As the 1950s ended and following the 1954 Brown v. Board Supreme Court decision, peer institutions such as Duke University, Emory University, Tulane University and Vanderbilt University experienced increasing debate on desegregation, according to Kean. Yet, Rice’s board of trustees kept their turmoil private and the Institute calm.

The growing push

The Thresher’s headline for the first issue of the 1960-61 school year, “President Takes Six Months Rest; [Provost] Croneis in Charge,” did not capture the vetting process occurring behind the scenes for Rice’s next president, Kenneth Pitzer. He took office at the newly renamed Rice University in 1961.

“Pitzer found the continuation of a racial bar in admissions at this time ‘just ridiculous’ and made it clear that he would not come to Rice, [and] could not do the job that Rice wanted done, if the ban on black admissions was not removed,” Kean wrote.

According to Kean, “the job” Pitzer planned consisted of graduate program expansions, building new infrastructure and pushing faculty recruitment. These projects required money — $33 million of it, which required federal funding and, as a result, desegregation. Pitzer himself received research funding from the AEC, the organization Rice had previously clashed with due to its nondescrimination requirements. Thomas and Brown had also continued their efforts with NASA, and in September 1961, a Thresher headline read, “NASA Research Center Definitely For Houston.” It was obvious to the board of trustees that desegregation was looming.

Charging students tuition would provide the school with another revenue stream and help modernize Rice University; at the time, it was one of only three schools nationally that remained tuition-free. This change, too, would be a deviation from Rice’s original charter, and completing these changes required a lawsuit against the charter.

As the discussion continued, some trustees felt admitting black students might result in fewer funds due to community opposition against integration, but Brown made it clear that funds, and therefore integration and tuition, were necessary for Rice’s expansion.

On Sept. 26, 1962, the board of trustees voted unanimously to file a lawsuit against the charter that would allow the admission of black students and charging of tuition.

As university leadership underwent internal turmoil, the student body’s discussion continued. In 1960, the sit-in movement had reached Houston, and the Thresher conducted a small survey of student opinion on the protests and published letters of varying support or condemnation. In February 1961, the Thresher took a strong editorial stance on the sit-ins after five Rice students were arrested.

“The Thresher endorses these few whose convictions on the immorality of segregation were strong enough to them to gravely responsible action outside the ivy-covered walls,” the editorial board wrote. “The responsibility for the arrest … lies with this community and all others like it which tolerate two classes of Americans.”

In December 1961, the Student Senate gauged student support through an election ballot referendum that showed 65 percent of students and 89 percent of faculty supported desegregation. Although students hoped this vote would be a push for change, the referendum had little if any impact.

Rice’s attorneys delayed filing the lawsuit — a delay that made much of the faculty and student body aware that change was coming soon, as Pitzer wrote to H. Malcolm Lovett, a member of the board.

“I am seriously concerned lest the faculty and student body come to believe that this action is being intentionally delayed,” Pitzer wrote. He urged that the attorneys file the lawsuit immediately.

Rice’s attorneys filed the lawsuit on Feb. 21, 1963, five months after the board gave its initial approval. The trustees’ petition argued that, without integration and the federal funding Rice could receive as a result of it, the school would be unable to fulfill William Marsh Rice’s promise to educate students.

Integration by trial

As the legal battle played out in the courtroom, students and alumni shared their concerns on the Thresher’s pages. Many of the conversations on tuition continue today.

“Will the scholarships that the university has promised to give reach … those students who are in the lower half or lower third of both the economic and the academic ranking?” Bill Edwards (’50) wrote in a 1964 op-ed questioning whether charging tuition would decrease Rice’s appeal. “Will they be large enough to enable these students, with what they can earn during summer and part-time, to maintain themselves at Rice?”

In a November 1963 interview with the Thresher, Lovett said 40 to 50 percent of the student body would always be on full scholarship.

“The racial barrier is as important as any, especially when it comes to government grants,” Lovett said, making no disguises about Rice’s need for funds.

Some alumni felt the trustee’s petition undermined William Marsh Rice’s will. John Coffee (’34) and Val Billups (’18) filed a lawsuit against the trustees in June 1963, claiming that the Trustees had no right to challenge the charter. Coffee and Billups said they did not disagree with integration or charging tuition, but sought to defend the founding documents of the school.

James L. Aronson (‘59) protested their actions by returning funds he had received under a scholarship named for Coffee back to the university.

“I can even less afford $100 today than I could in 1957,” Aronson wrote in a private letter to Coffee. “As a peaceable protest to your action I am returning this money to Rice, and asking that the John B. Coffee Scholar in Geology award be removed from my record. Legally, you may be right, but morally you are not.”

Other alumnus filed a petition supporting the trustees. Coffee and Billups’ suit endured for years until 1967.

As the legal battle continued, Rice felt the consequences of the delay. The university nearly lost the Naval ROTC program and the NASA contract.

Graduates and undergraduates alike showed support for the matter through a petition with 1,181 signatures given to Rice’s lawyers, as the Thresher reported in February 1964. Weeks later, on March 9, 1964, the court’s ruling gave Rice the official power to alter its charter.

The university admitted the first black graduate student, Raymond Johnson, to study for a master’s degree in mathematics in the same year. Johnson later returned as a professor in 2009. President Pitzer told the Thresher that black undergraduates would be admitted and tuition would be charged starting in fall 1965.

The first black undergraduates

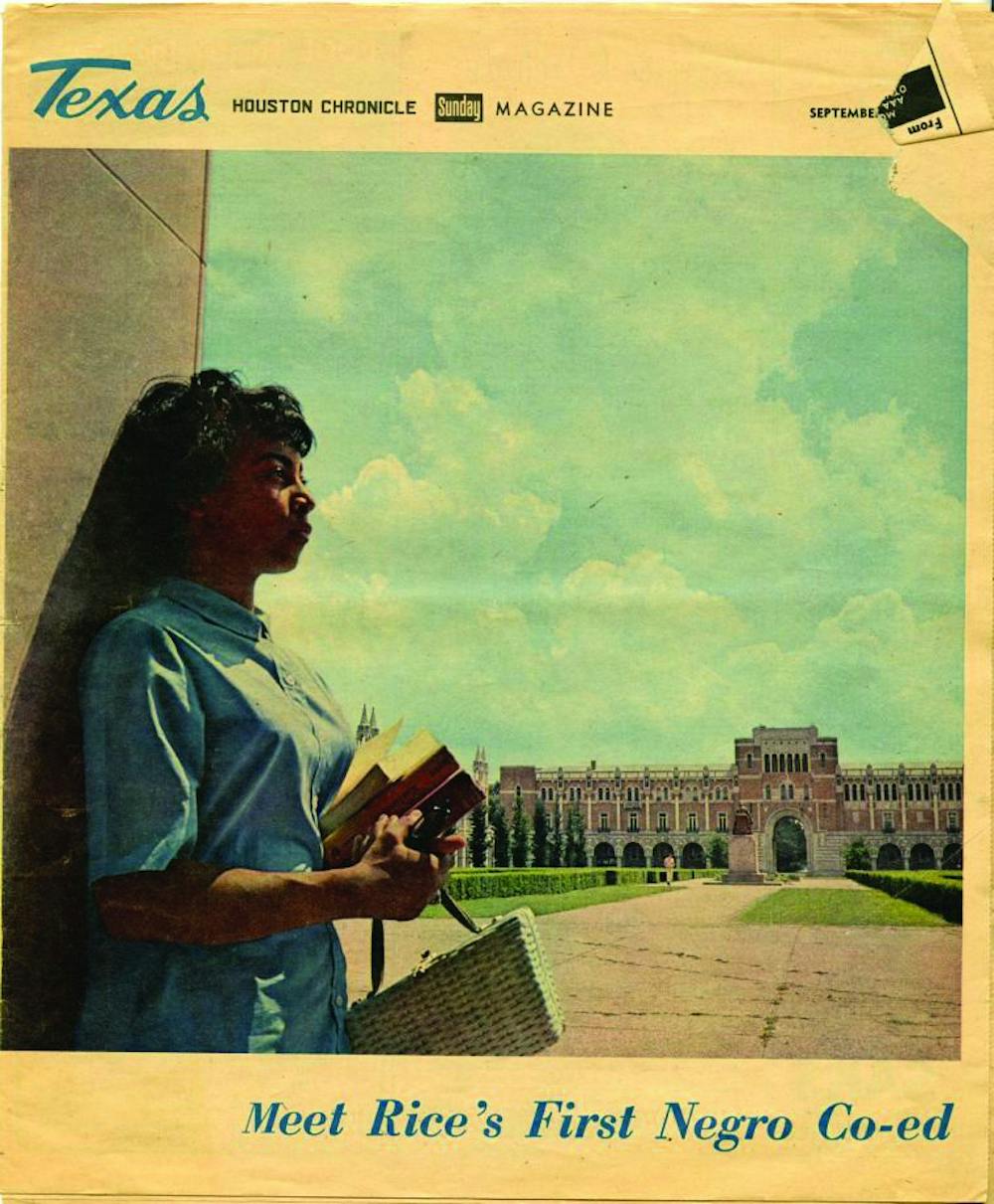

In its first issue of fall 1965, the Thresher reported that five black students applied to Rice. All were admitted, and two, who remained unnamed in the article, chose to attend. Of these two students, neither Charles Edward Freeman III nor Jacqueline McCauley graduated from Rice. Freeman transferred to Texas State University, a historically black college, and ultimately graduated from Lamar University. McCauley went on to be a radio host on Houston’s KLOL.

Considering the preceding decades of discussion, there is surprisingly little formal documentation in the Thresher about these first black undergraduates. Thresher archives do show that McCauley was active in theater at Rice. She played the lead in “The Perils of Pomona,” a play about a Native American woman forbidden from interracial marriage.

The Thresher’s review of the performance provides a small window into her experience.

“She falls in love with a wealthy planter, but is doomed to be sold on the block as a slave,” the preview to the play reads. “The villain wants to buy Pomona for his own evil purposes. Will he succeed in buying her at the slave auction? Is Pomona doomed to a life of degradation and misery? Can [the hero] save her? The Jones production will provide all of the answers this weekend.”

Neither the Jones production nor the Thresher archives, however, could answer the questions Rice so deeply needed to ask following integration. What were Freeman’s and McCauley’s daily sources of courage as they paved the way for future generations of black students? What was their “Rice experience?”

More from The Rice Thresher

Worth the wait: Andrew Thomas Huang practices patience

Andrew Thomas Huang says that patience is essential to being an artist. His proof? A film that has spent a decade in production, a career shaped by years in the music industry and a lifelong commitment to exploring queer identity and environmental themes — the kinds of stories, he said, that take time to tell right.

Andrew Thomas Huang puts visuals and identity to song

Houston is welcoming the Grammy-nominated figure behind the music videos of Björk and FKA twigs on June 27.

Live it up this summer with these Houston shows

Staying in Houston this summer and wondering how to make the most of your time? Fortunately, you're in luck, there's no shortage of amazing shows and performances happening around the city. From live music to ballet and everything in between, here are some events coming up this month and next!

Please note All comments are eligible for publication by The Rice Thresher.