50 years later, Rice’s first Black student-athletes reflect on their impact

Stahlé Vincent came back to Rice over the weekend. But this time, he got a different reception than he did when he first set foot on campus over five decades ago.

“[When I first got here] there was not an open-arm reception,” Vincient said. “There were people who never spoke [to me], people avoided me, I had professors who wouldn’t call my name at roll. There was an animus there that you could feel.”

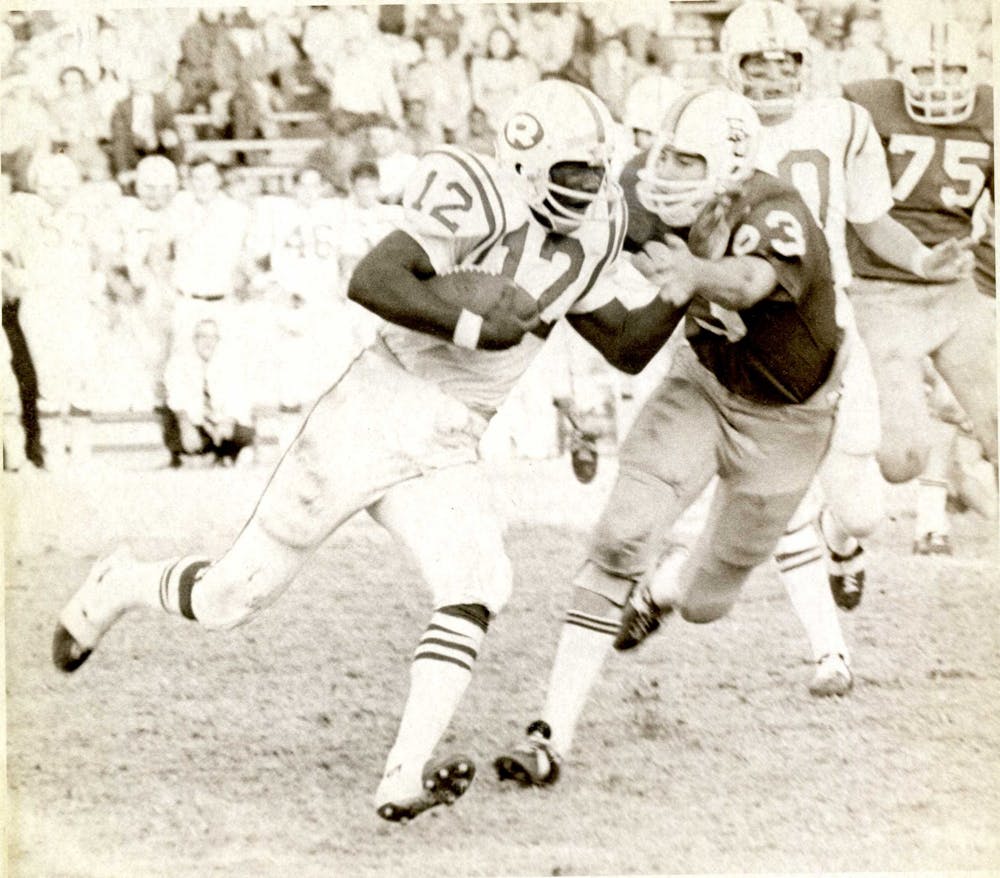

Vincent, a member of the first class of Black student-athletes at Rice, was among six alumni to be honored on Friday for their role in integrating Rice athletics. Vincent (’72), along with Rodrigo Barnes (’73) and Mike Tyler (’72) of the football team, along with Leroy Marion (’72) of the basketball team, were recognized for being the school’s first Black student athletes, while former volleyball player Denise Bostick (’80) and runner Leila Freeman (’79) were honored for being the first Black female Owls. According to Vincent, the event came together after he wrote a letter to athletic director Joe Karlgaard and deputy athletic director Rick Mello during the fall of 2020.

“I was watching a game day pregame show,” Vincent said. “[It was] 2020, the pandemic, Black Lives Matter, the whole bit, and athletics is taking the forefront, because schools are going around honoring their first African-American players. I’m thinking, ‘what about us?’ So I wrote a letter.”

The event coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of the class of ’72, of which Marion, Tyler and Vincent were members. According to Barnes, who graduated a year later, seeing the progress made in the half-century since his time at Rice was much more rewarding than the honor itself.

“I am thrilled because I know how it got started, and I know the sacrifice I paid for it,” Barnes said.

When he first arrived on campus, Barnes said it was clear that he wasn’t particularly wanted there.

“Rice was trying to make an adjustment to get the NASA money, so they invited us,” Barnes said. “It wasn’t because they loved us or anything … It was economic. They did not attack me. There was no [Ku Klux Klan] coming at me on campus. There were people individually that did a lot of small, stupid, silly things.”

Specifically, Barnes rememberers facing blatant discrimination in the classroom.

“In the textbook it said I was inferior,” Barnes said. “In the science book it said I was incapable. The answer to the question on the test was [that] I was inferior and not capable.”

Even though they arrived on campus just a few years later, Bostick and Freeman said that they have mostly pleasant memories of their time at Rice.

“There was some racism on campus,” Bostick said. “But it’s something about athletes, that, even though I was the first Black woman – and really, to be honest, I didn’t even focus on that – but when you’re an athlete, [I felt that] the racism is not as prevalent because you have a … common goal [with your teammates].”

According to Freeman, her background growing up in a military family helped prepare her for being one of the only Black women athletes at Rice.

“I may be very naive when it comes to that, but I never felt out of place,” Freeman said. “I never did, because my background is this: I’m a proud Black person, but I was raised in a military family … I was always in an integrated situation. And I felt that was normal. People just didn’t make me feel different, as far as I could see.”

Vincent, on the other hand, said that the few Black student athletes at the time often had to lean on each other for support.

“A couple of times a week, Rodrigo, Mike Tyler and my roommate, we’d get together and prop each other up, because we made a decision to come here,” Vincent said. “We’re gonna make it work. But psychologically and emotionally … I was not ready for what I encountered.”

However, like Bostick and Freeman, Vincent said that he also found more acceptance when he was among his teammates.

“It was much better with my teammates,” Vincent said. “Because if we look at the sports arena, if you can play, it doesn’t matter. Rodrigo, Mike, and I — I’m not gonna brag, but we could play — so whether you like it or not, we were going to help the team win. Therefore, [teammates would think] you need to play and we need to support you.”

Barnes went to great lengths to create community and resources for Black students on campus. According to Barnes, he was a founder of the Black Student Union, served as its first president, and helped organize a protest to spur the hiring of more Black staff members.

“We [once] picketed the halftime of a basketball game,” Barnes said. “They got worried. They decided to hire a Black coach, and they hired a Black person to work with the kids as a psychiatrist.”

Barnes said that he faced backlash for his activism, even well into his NFL career, but at a certain point he thought the school had no choice but to accept him.

“I made all-conference, but my school didn’t promote me to be all-American,” Barnes said. “They were offended because here is a 19 year old, 20 year old kid forcing them to have Black coaches, Black professors, recruit a few more [Black] students, to change the culture … I was kind of like the enemy on campus. But they had to tolerate me because of who I was athletically and as a person.”

Vincent said he took a different approach at first, focusing primarily on his responsibilities in the classroom and on the field.

“Talk about being a trailblazer, during the first part of my sophomore year, it was just background noise for me,” Vincent said. “I had [tunnel vision]: it was football, school and doing well.”

However, a few games into his first year, Vincent realized the kind of impact he was in position to make.

“My first four games were pretty bad,” Vincent said. “And so I'm going, ‘why am I here?’ [Then] I started getting letters from all over Texas – school administrators, principals, teachers, parents, and high school student-athletes. And they said I made it cool to be a good student and good athlete again, so keep up the good work.”

Freeman also said that she wasn’t focused on being a trailblazer. When she first got to campus, Freeman was an avid runner but didn’t have time to compete in Division I sports, and Rice was still three years away from forming a women’s track team. However, after spending a year studying Paris, Freeman had earned her associate’s degree and used that as a bargaining chip to convince her parents to let her run.

“[I said,] ‘well, if I go back, I'm going to run track,’” Freeman said. “And so they said, ‘sure, we just want to see you finish.’ So that's how I came to run track. So to me it was just living my life and doing what I loved. I didn't think I was going to be recognized other than maybe win a few races. But I never thought that I was being a groundbreaker at that time.”

Bostick said that when she started to reflect on her role in Rice history, she is proud to have helped create opportunities for Black athletes down the road.

“To be a part of, you know, when I look back, and I start reflecting, you know, I've gone through the Black history of rice, and the rice alumni… The first Black [women’s] basketball scholarship athlete was Goya Qualls a year or two after me … [Today] they have a lot more tools that they're given these young ladies, to be able to really succeed and get everything that they need … To be a part of furthering that is just a real blessing.”

Being back on campus, Vincent said, has reminded him how proud he is to have contributed to the success of countless Black athletes.

“When I see the young brothers and sisters who said, ‘going to Rice has been an integral part of my success,’ I feel like I played a small role in that,” Vincent said.

According to Barnes, despite his complicated relationship with the school during his time on campus, he loves Rice and is happy to know he helped it change for the better.

“When I came to Rice, when I rolled through the front gates off of Sunset and Main, and looked at Lovett Hall, I fell in love with Rice,” Barnes said. “So I was committed to help it be one of the best that it could be. The things I did [were] to help Rice ... Look at them now.”

More from The Rice Thresher

Rice football wins season opener under new coach

For the first time since 2018, Rice football opened its season with a victory. Scott Abell was soaked with yellow Powerade following a 14-12 win on the road Saturday against the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, which won 10 games and made it to the Sun Belt Conference championship last season.

Students see expanded merch and restaurant discounts

The Campus Bookstore will now offer a 30% discount to any one apparel item on the first Friday of every month, a change from the previous 10% discount on a designated “spirit item” introduced last April, according to an Instagram post by the Student Association.

Review: Contemporary Arts Museum exhibit recolors American vision

Color, the artist and educator Josef Albers theorized, is relative. A red square flanked by yellow appears orange; surrounded by blue, it looks purple. Rather than being absolute, color behaves in constant flux. In “Tomashi Jackson: Across the Universe,” the titular multimedia artist extends this principle to racial categorization, suggesting that race, too, operates through relational mechanisms.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication by The Rice Thresher.