An abstraction of being: Seeing Rothko

An advertisement for a new Rothko retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, that will run until Jan. 20, 2016. The exhibition will feature over 60 pieces spanning the entirety of Rothko’s career.

Perhaps you’ve heard of the name, or perhaps you recognize those monolithic hazy blocks of color. Mark Rothko has long been considered one of the most infl uential artists of the 20th century. An austere earthy-colored painting of his, descriptively titled “Orange, Red, Yellow,” sold for a record price of $86 million in 2012, and remains, to this day, one of the most expensive works of modern art.

This past weekend saw the opening of a retrospective of Rothko at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. According to assistant curator Althea Ruoppo, “[This] is the largest presentation of Rothko’s work seen in the United States since the National Gallery retrospective of 1998.” But how did such simplistic pieces reach such a high status in the art world? What is the point of these abstract compositions? Here is a primer to understanding Rothko.

Rothko, born in 1903 as Markus Rothkowitz, grew up in a Jewish family that emigrated from Dvinsk, Russia, to Portland, Oregon in 1913. The value his family placed on education enabled him to commence his studies at Yale University, yet he dropped out after his sophomore year and moved to New York, where he began painting under the tutelage of Max Weber in the Art Students League; here, Rothkowitz was exposed to modernism and the American avant-garde and befriended Jackson Pollock and others whom the world would later know collectively as the abstract expressionists.

The early works of Rothkowitz were strongly inspired by cubism, fauvism and German expressionism, and featured dynamic brushwork, saturated colors and distorted shapes characterize these paintings. In 1940, he began to use the name Rothko, and early in that decade produced paintings infl uenced by the surrealists, in particular Joan Miró. Rothko was fascinated with the surrealist concept of mining the subconscious to produce art that was deeply provocative and visceral. His art during this period were full of ideograms and motifs, a testament to his intellectual exploration of religious and mythical symbols, which he felt could reveal obscure and intricate inner truths, a postulation perhaps inculcated in Rothko by the Jungian notion of the “collective unconscious.”

In June 1943, Rothko, with fellow artists Adolph Gottlieb and Barnett Newman, penned a now-famous letter to the New York Times articulating their artistic beliefs: “We favour the simple expression of the complex thought … There is no such thing as good painting about nothing. We assert that the subject is crucial and only that subject matter is valid which is tragic and timeless.” From then on, Rothko began to move toward abstraction as he, in his words, “pulverized the familiar identity of things.” Ethereal patches of color and chromatic clouds su used his paintings and swept away discernible relationships of form and structure. As he manipulated its space, volume and lambency, color replaced fi gure as the subject of the canvas and became a portal for the search of universal truths. By 1950, Rothko’s compositions were constituted of two or three rectangular slabs of color, layered and hovering above one another and fi lling up enormous vertical canvases. These would later be recognized as his mature style. The simplicity of these paintings, according to Rothko, allowed him to “[eliminate] ... all obstacles between the painter and the idea, and between the idea and the observer.”

Rothko proclaimed, “I’m not interested in the relationship of color and form or anything else. I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions: tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on.”

This emotional content was conveyed through the tone, depth, contraction and expansion of glowing masses of hue. Viewers experience psychological tension at once disembodied yet absolute, attesting to his work as transcending the physical and becoming a conduit to a higher spiritual plane.

Rothko preferred smaller rooms to museums for exhibitions, such that “the largest pictures … must be fi rst encountered at close quarters, so that the fi rst experience is to be within the picture.” He also insisted that his paintings be hung as close to the fl oor as possible, unframed, in groups, never together with works by other artists, and in lowlit spaces with o -white walls. 18 inches was, according to him, the ideal viewing distance. When we look at them under these conditions, Rothko’s paintings seem to swell beyond the borders of the canvas, enveloping us.

The MFAH’s retrospective includes more than 60 of Rothko’s works, drawn from his entire career and tracing all of his major artistic developments. It provides an unrivalled opportunity for Rice students to explore the most compelling works from this most enigmatic and extraordinary of artists.

“Rothko’s works are so important ... because they are timeless and universal,” Ruoppo said. “Rothko made the viewer his priority; he wanted you to have a personal experience with his paintings. Perhaps his greatest achievement was creating an art that continues to resonate with you.”

Through his art, Rothko wanted us to face the mysterious abyss in our souls and grapple with the indescribable nuances of human tragedy.

The exhibition will be on display at the MFAH until Jan. 24, 2016.

More from The Rice Thresher

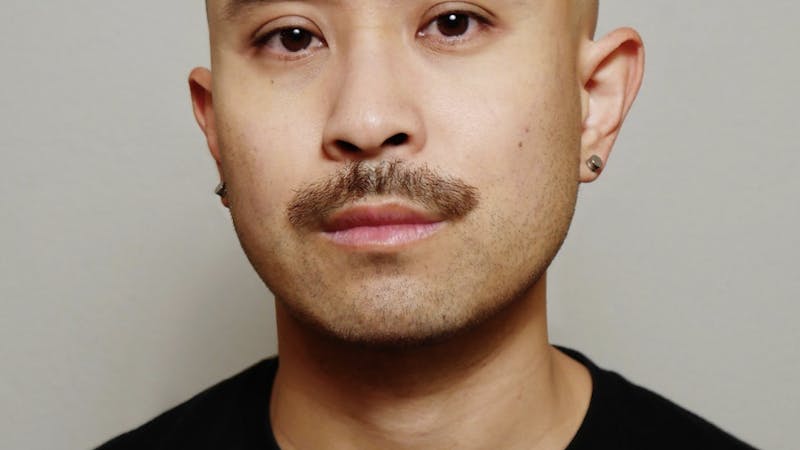

Andrew Thomas Huang puts visuals and identity to song

Houston is welcoming the Grammy-nominated figure behind the music videos of Björk and FKA twigs on June 27.

Live it up this summer with these Houston shows

Staying in Houston this summer and wondering how to make the most of your time? Fortunately, you're in luck, there's no shortage of amazing shows and performances happening around the city. From live music to ballet and everything in between, here are some events coming up this month and next!

Review: 'Adults' couldn’t have matured better

Sitcoms are back, and they’re actually funny. FX’s “Adults” is an original comedy following a friend group navigating New York and what it means to be an “actual adult.” From ever-mounting medical bills to chaotic dinner parties, the group attempts to tackle this new stage of life together, only to be met with varying levels of success.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication by The Rice Thresher.